By Kara Baskin

Recently, I got a text from a friend who lives in a rural part of central Massachusetts, down a long driveway. A swastika had been spray-painted at the foot of her street. She had no idea who did it; the symbol was a chilling reminder of the anonymous hatred that lurks even in quiet, supposedly safe places. Although her neighbors attempted to erase it, the hauntingly faded outlines remain.

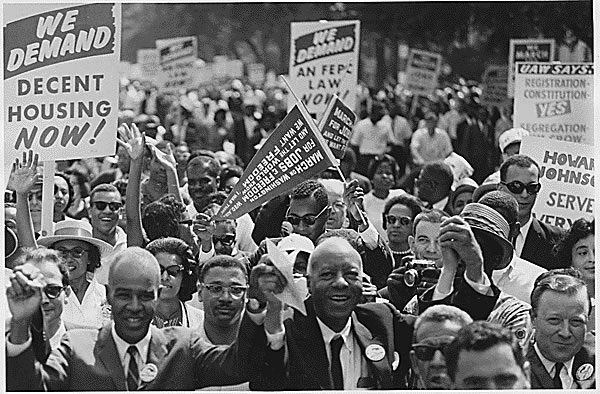

These instances are numerous and often far more out in the open. In 2022, ADL tabulated 3,697 antisemitic incidents throughout the United States. This is a 36% increase from the 2,717 incidents tabulated in 2021 and the highest number on record since ADL began tracking antisemitic incidents in 1979.

In this climate, it’s easy to become inured to this kind of hideousness. To paint over the ugliness and move along. But we can’t. We have to act as though every time is the worst time, that every incident is disgusting, to resist complacency. I talked to The Rashi School middle school dean Joni Fishman and ADL New England deputy regional director Peggy Shukur about how to do this, especially with kids, as incidents become more prevalent.

“Some call antisemitism the oldest form of hatred,” Shukur says. “It’s something that feels more frequent judging by the types of incidents we’re getting, and it demands that parents have conversations with children.” (If you have experienced or witnessed an incident of bias, hatred or bigotry, you can report it here.)

Explain what a swastika is. Whenever possible, teach.

In this era, the symbol is notorious, but what does it truly mean? As more and more Holocaust survivors die off, the chilling significance of the symbol as the emblem of the Nazi party can lose its meaning, recognized merely as an easy means to instill fear.

“People have chosen a symbol that’s widely recognized as one of the most notorious hate symbols in Western culture, whether they know details about the Holocaust or not,” Shukur says. Some kids might even doodle it, not knowing what it is. Tell them. Says Fishman: “When I once asked a young person, ‘What does a swastika mean to you?’ they responded, ‘Well, it’s one of those things you see, and it’s not so nice.’ Not so nice!” Some people truly might not understand the true weight of the symbol. As we move further and further from the Holocaust, she says, we need to educate whenever we can.

Words have power, and actions matter.

We’re inundated with news around the clock; we can fire off tweets and reduce sentiments to hashtags. It’s easy to simply say, “Just kidding! I didn’t realize!” Fishman says. But even now, especially now, words still matter. Conversations still matter.

This is especially important for young people. Talk to your children. Ask them, “What have you seen in the news? What are you thinking about? What are you worried about?” she says. The delivery mechanisms for information might have changed, but the human capacity to make sense of it all hasn’t evolved along with it. Pause to check in with your kids.

Yes, we live in a scary world. Antisemitism and other forms of hate have been rising, and the impacts of climate change and gun violence are also threatening. If your children come home scared, “You can always listen,” says Fishman. “Say, ‘Tell me what’s on your mind. Is there anything specific you’d like me to do?’ Don’t jump into, ‘I’m going to fix this,’ but offer tools to help them feel safer,” whether that’s explaining safety measures their school has taken or helping them to understand where hate and bias come from in the first place, so it’s less sinisterly mysterious. There are tools available to help have these conversations not only with your children, but also with adults who need support.

Use the ADL’s Good Fight toolkit.

This is a 30-page, easy-to-read primer on antisemitism. What is it? Why does it exist? How do we fight it while also protecting our own safety? What are the origins?

The toolkit explains: “Systemic antisemitism has existed since ancient times, originating as religious intolerance after Christianity became the central religious, cultural and political force in medieval Europe. Following the development of ‘scientific’ explanations for race, Jews were seen as a biologically inferior and distinct group, oftentimes a justification for isolation and expulsion. Central to antisemitism is the myth that Jews are to blame for society’s problems.”

The free download offers a helpful grounding framework; it’s a comprehensive resource on how to respond to hate—ways to talk to your children about what they might see and hear, how to press peers if they make antisemitic comments and how to report incidents. Read it.

Kara Baskin is the parenting writer for JewishBoston.com. She is also a regular contributor to The Boston Globe and a contributing editor at Boston Magazine. She has worked for New York Magazine and The New Republic, and helped to launch the now-defunct Jewish Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Email her at kara@jewishboston.com.