The COVID-19 pandemic was heavy enough.

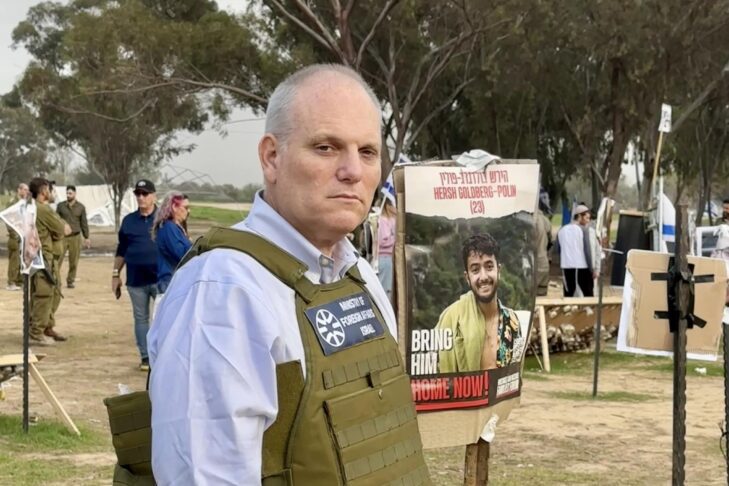

As a practicing physician and the Chair of the Salem Board of Health, Dr. Jeremy Schiller was doing his utmost to protect community members from a virus scientists were racing to understand and navigate in real time.

“I had a good relationship with [then Mayor of Salem] Kim Driscoll, and we promoted COVID mitigation strategies that were rooted in science and were progressive and dynamic,” Dr. Schiller says. “Despite overwhelming support from the community, we received a lot of the typical negative responses — and I was ok with that. Science is hard and is always evolving and that is not easy for some to digest and understand.”

However, those responses became personal in December 2021. The Omicron variant was sweeping through Massachusetts and hospitals were dangerously nearing full capacity. The Salem Board of Health, at the urgence of local hospital leaders, instituted a vaccine mandate for local restaurants to help keep area hospitals from a possible catastrophic crisis.

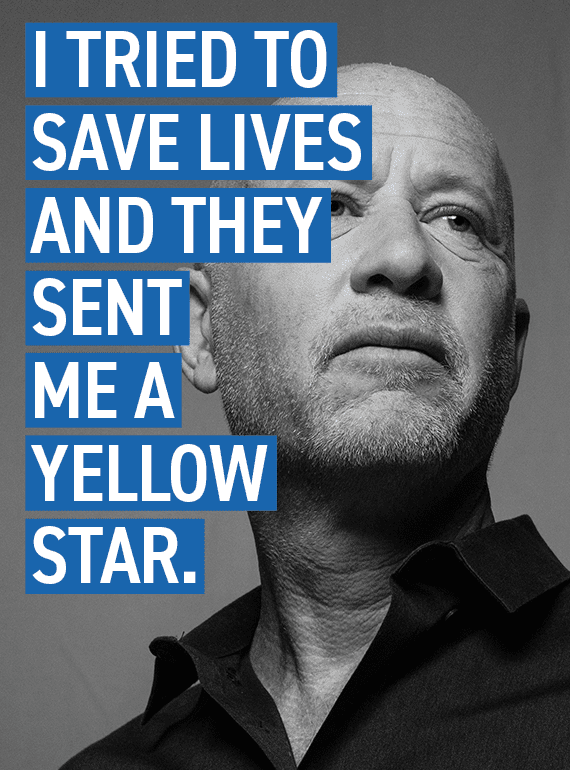

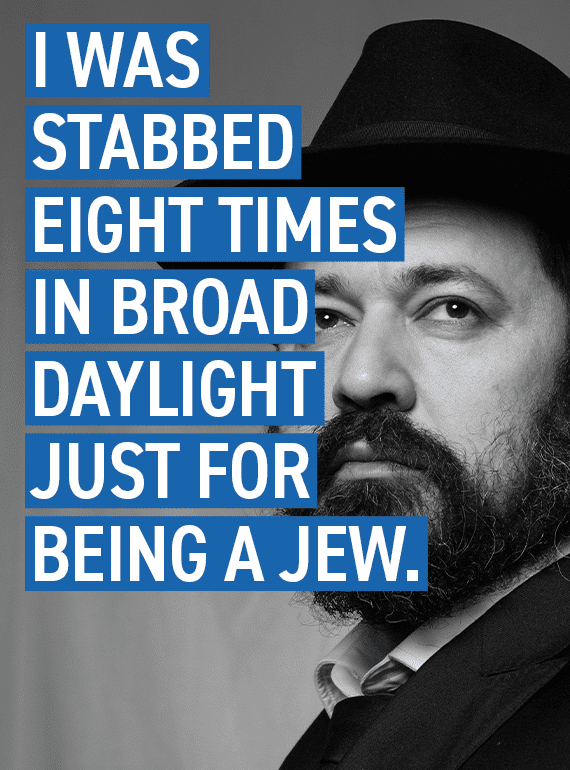

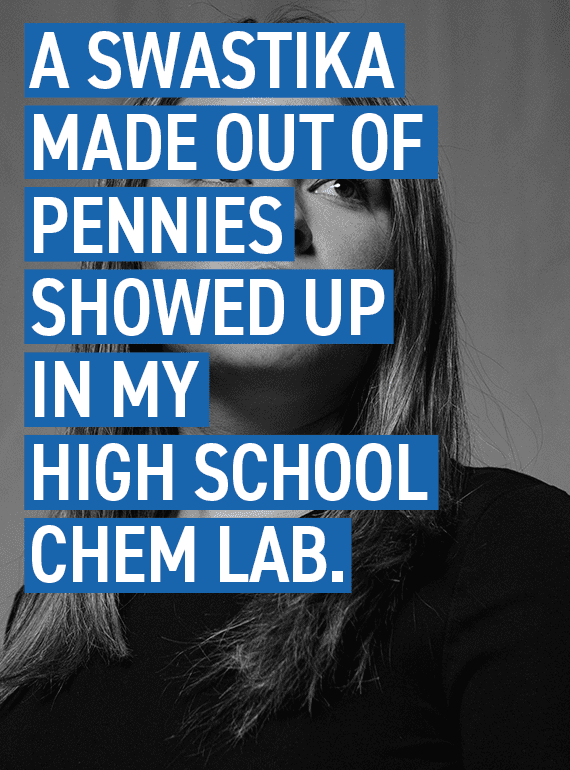

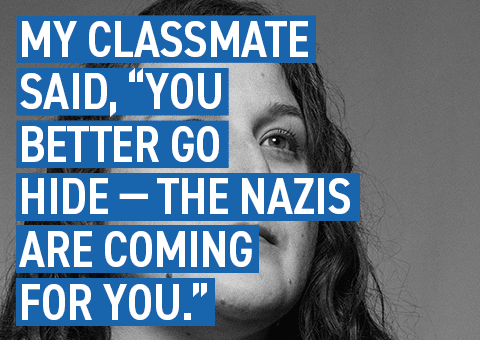

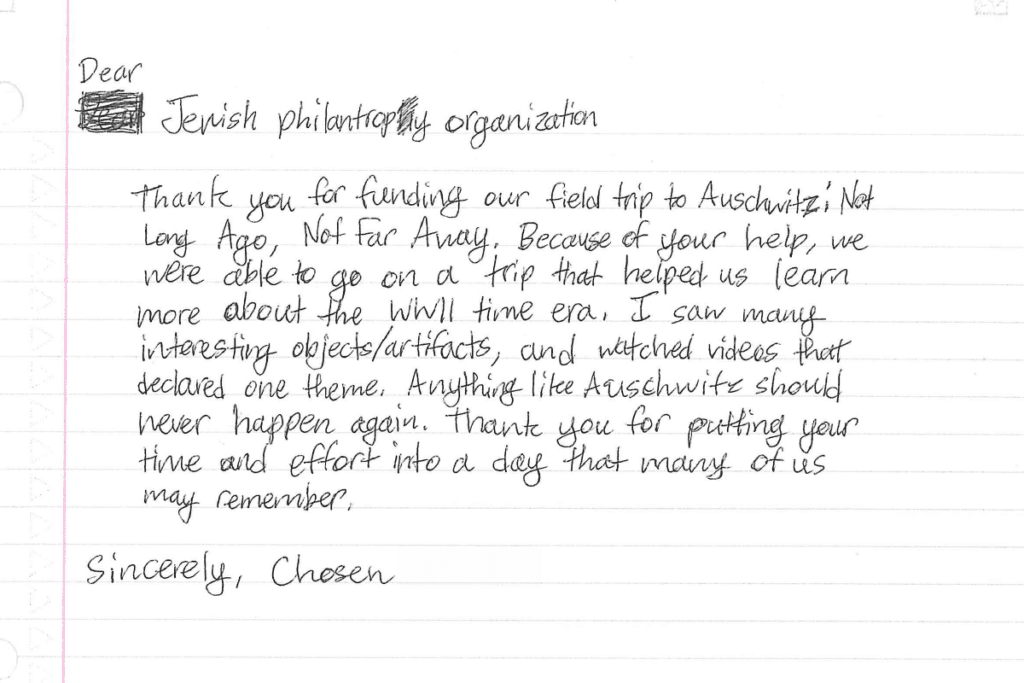

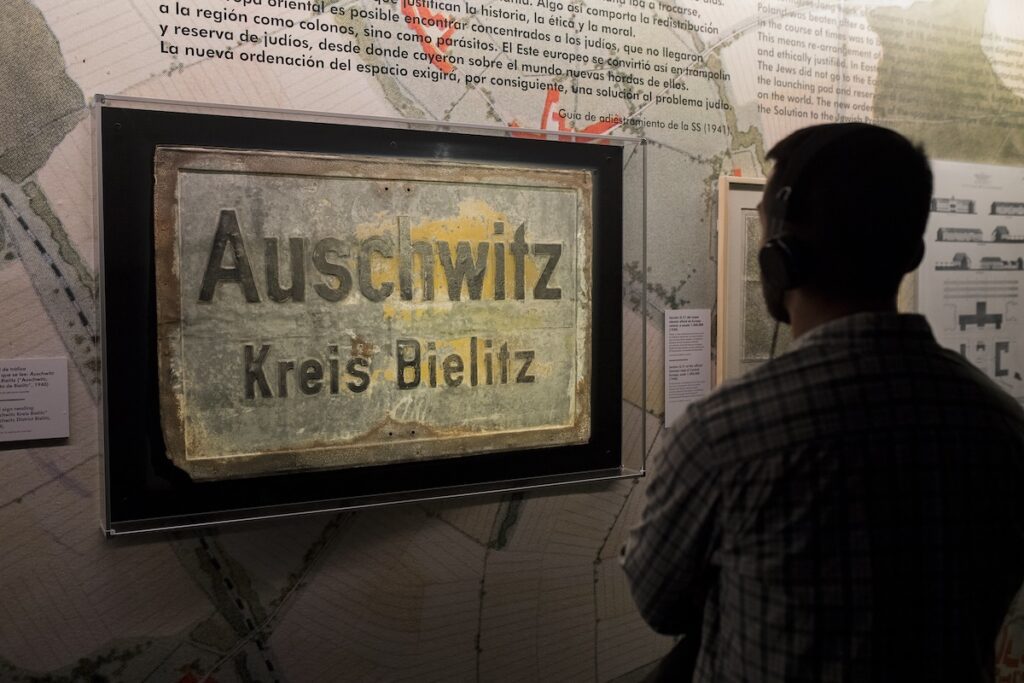

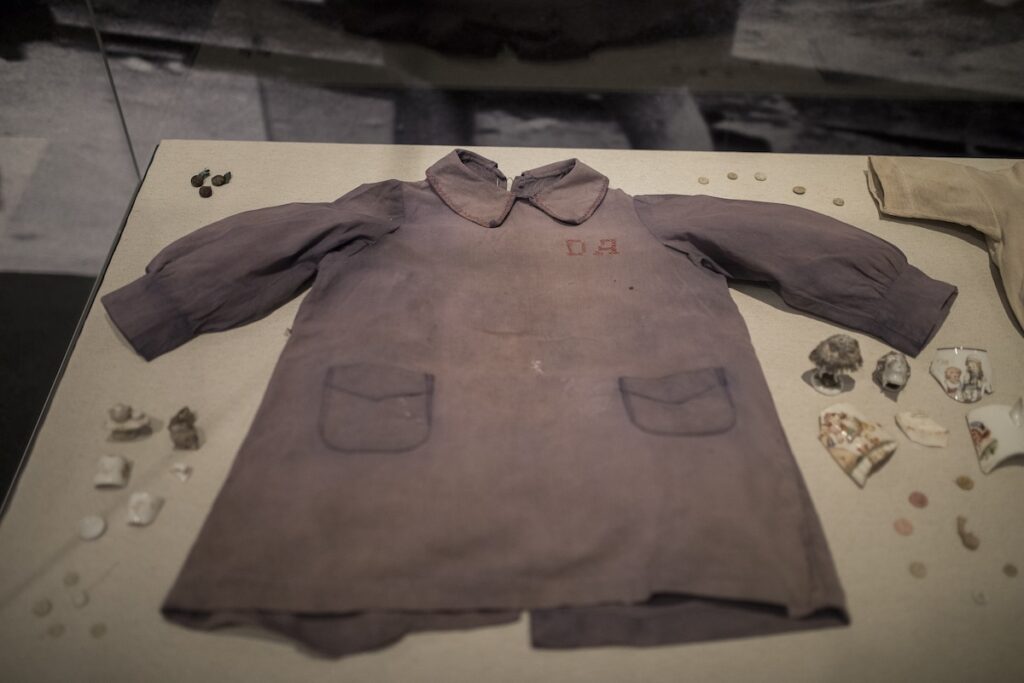

“At that point, there was a real increase in number of those comparing what we were doing to the Holocaust,” Dr. Schiller remembers. “Multiple emails on a daily basis from various people in the community.” Dr. Schiller went out of his way to respond thoughtfully to the emails and educate community members on the actions the Board was taking. However, the correspondences were becoming increasingly antisemitic in nature. Salem’s Health Agent, whose surname sounds Jewish, shared that both he and Dr. Schiller had been the subject of voicemails citing them as “Jews controlling public health.” He also forwarded Dr. Schiller postcards the Board of Health had received that were addressed to “Un ‘Doctor’ Schiller” with a Star of David drawn on it and statements like “FREI” (German for “free”), “GENOCIDE,” and “Justice will come for you” scrawled across them. The Health Department even received a yellow Star of David — badges Jews were forced to wear in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Around this time, a rally was held outside Dr. Schiller’s house (he wasn’t there), organized by Diana Ploss, an independent gubernatorial candidate who, later that week, livestreamed a simulcast of the Board of Health meeting, with hateful comments like, “Look at this Jew, always after money” and “Look at the smug Jew talking” posted on her website. Dr. Schiller, who volunteers in his position as Board Chair, was aghast and disgusted that his efforts to help guide the community safely through the pandemic evolved into an opportunity for antisemites to viciously attack him for the simple fact that he is Jewish.

“It was scary,” Dr. Schiller says. “I contacted Mayor Driscoll and there was no political calculus whatsoever on her part. She immediately released a letter along with the ADL condemning what was going on.” Dr. Schiller also applauds the swift response of Chief Lucas Miller of Salem Police Department in coming to his defense, as well as the President and Chief Executive Officer of Beth Israel Lahey Health, Dr. Kevin Tabb, for reaching out and supporting him.

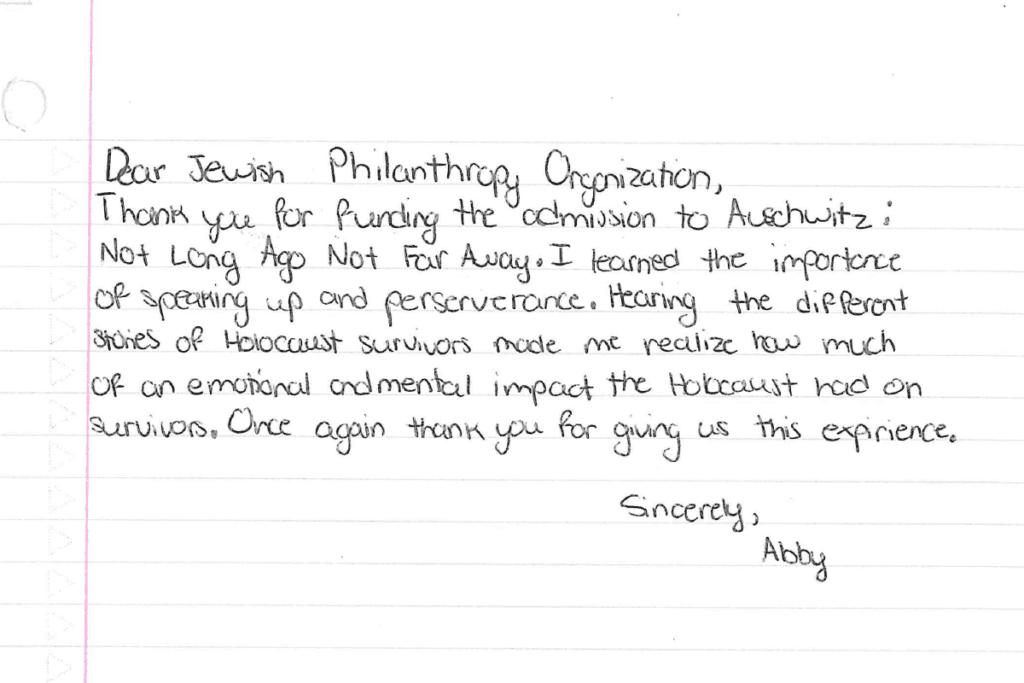

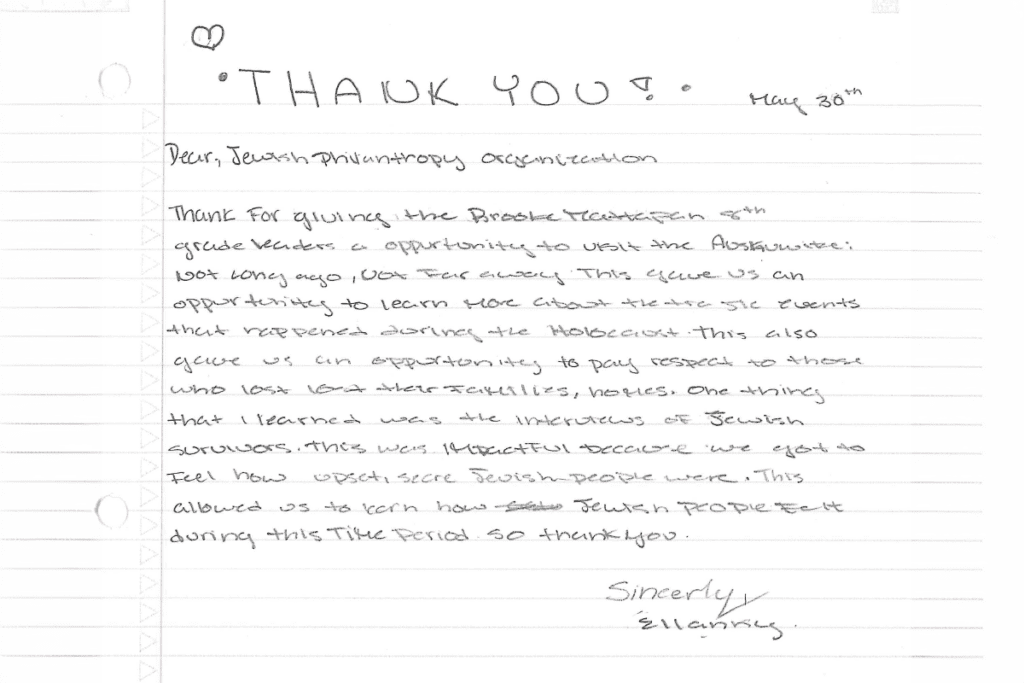

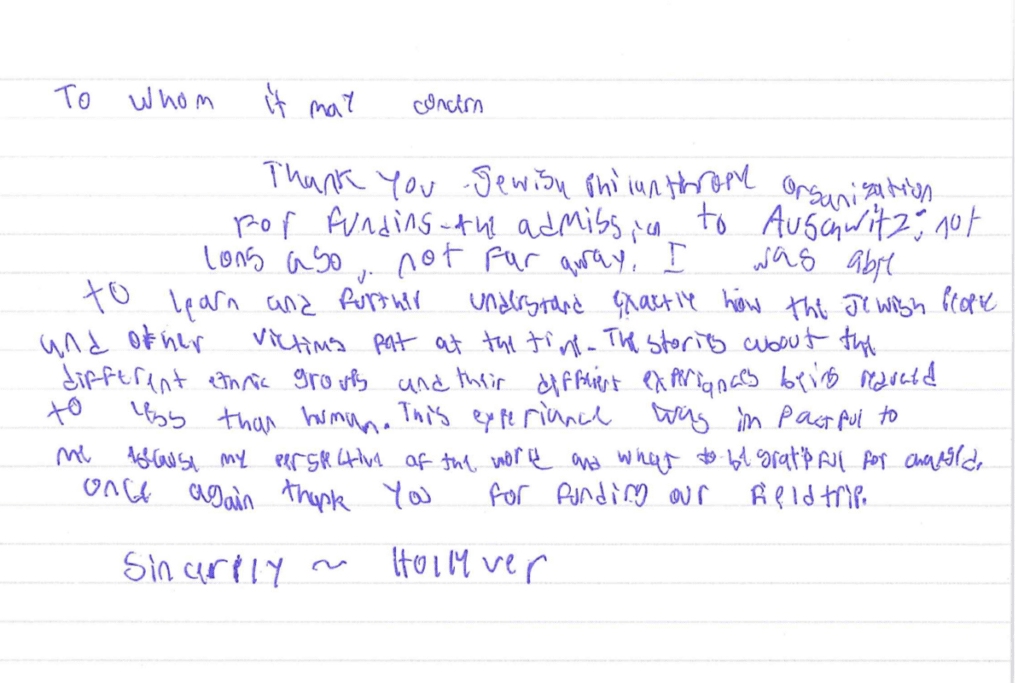

“To me, there’s a role for condemnation and outrage, but it can’t end there. Education and understanding are critical components to combating antisemitism and hate,” Dr. Schiller says. “That’s why the idea of allyship is so important to me. We can only imagine how many other groups of people feel marginalized. I have a very close family and amazing friends. I can’t imagine how deeply undercutting and painful this would be to someone who doesn’t have that kind of support — because even with that support I can still feel the pain of it today.”

Share your story

Share your story